Completely unrepresentative conversations over different drinks have revealed that, regardless of the drink, the prevailing view is that there are many dependencies in many companies.

This article sheds light on what is going on and what can be done about this situation. It is, so to speak, addiction advice for the organization. Against addiction!

Slow down a bit! What is this dependency anyway?

Maybe the picture is not enough to explain it. There's just more text and fewer pictures to explain it. A dependency is a causal referentiality of two or more entities. This means that at least two things are connected for an addiction. Two things can be anything from man and alcohol to moon and tide to work package A and work package B. Causal referentiality means that there is a necessary connection between the entities in at least one direction, possibly both. In other words: If A occurs, B follows. Vice versa, A may also follow if B occurs first.

More specifically for dependencies in the context of work, there is a minimalist definition:

Furthermore, we define dependency as a situation that occurs when the progress of one action relies upon the timely output of a previous action or the presence of a specific thing.

Strode & Huff: A Taxonomy of Dependencies in Agile Software Development

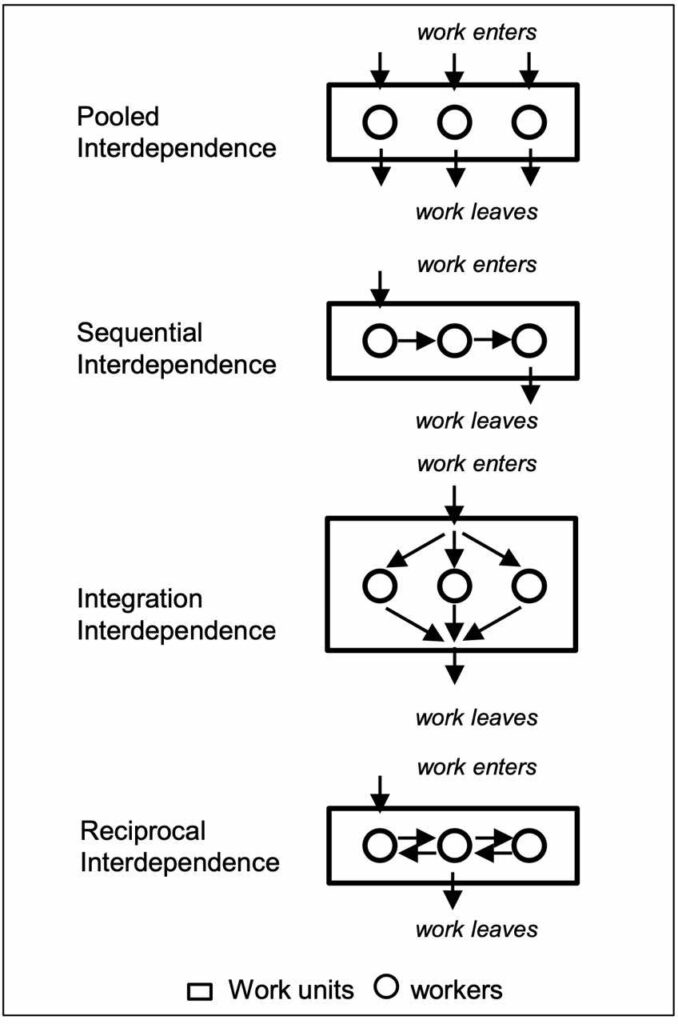

The dependencies can have different characteristics. The following image shows possible categories; several of these dependencies can also be mixed.

So far, so theoretical.

Dependence in practice

In development and service, dependencies can almost always be reduced to a single factor: Knowledge.

The more knowledge-intensive development becomes, the greater the challenge. In this article, I have derived the increasing knowledge intensity in value creation.

I've written "almost" a few times, so let's take a look at the exceptions: There are physical dependencies in production and logistics; I can't ship a pallet if the goods haven't been packed first. Similarly, there are simply physical dependencies in production; a car body can only be galvanized once it has been welded/glued.

In development, there are far fewer cases in which these physical dependencies cannot be solved procedurally.

Examples: A 3D printer for metals, in particular for printing titanium alloys, was required for the development of a robotic arm. This resource was occupied most of the time in the company and therefore a time dependency.

In another case, I was involved in lubricant development (exciting: hydrocarbon with graphene) and the use of the test laboratory was only possible to a limited extent.

In contrast to these physical dependencies, dependencies in knowledge-intensive environments can usually be avoided and resolved more easily!

Four ways to deal with dependencies

- Ignore it. This does not eliminate the dependency, but at least it does not take up any energy for a while.

- Coordinate. By recognizing dependencies as such, actions can be adapted accordingly.

- Avoidance. Dependencies can be avoided ex ante through better organization and technology.

- Solve. If causal referentiality is removed, each entity can exist on its own.

I hope it's just my experience, but in the organization of work, I unfortunately encounter options one and two most often. Why unfortunately? That's quickly explained. Coordination generates effort that does not directly contribute to value creation. And so, strictly speaking, it is a waste. Don't you think so?

Alternative 1: You can hold a large coordination event on a regular basis. At this event, you have two to three days to coordinate all dependencies in your software architecture and release management.

Alternative 2: The technological and organizational capabilities enable a variety of aligned and independent actions at the same time; the software architecture allows continuous deployments.

Which scenario do you choose?

Of course, in practice the second alternative is desirable, but alternative one is still necessary because of the technical and organizational legacy. My point is: maintaining alternative one probably costs more over time than alternative two. It certainly costs nerves, and sometimes even the chance to tackle a new development at all. It's the recurring consideration of how much do I have to invest in the ability to deliver so that I can deliver appropriately?

Interestingly, ignoring is not necessarily the worst option. If I ignore a dependency and still achieve the individual goal for all dependent entities, then the dependency wasn't one after all, wasn't that important or someone is a master of improvisation. If ignoring doesn't help after all, coordination is still possible. A dark figure for unrecognized and therefore ignored dependencies would be exciting!

This reveals another disadvantage: dependencies that cannot be ignored cause delays. The waiting time caused by them is usually longer than the time required for coordination.

Dependencies Solving is silver, avoiding is gold

Now that we have looked at how to deal with dependencies, I will focus the rest of the article on avoiding and resolving dependencies.

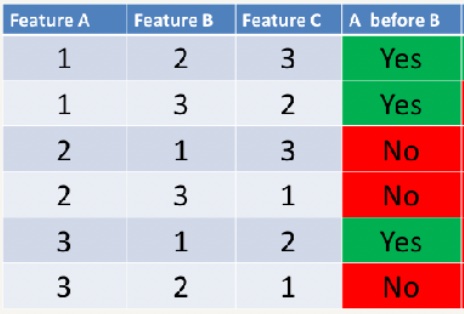

Let's start with a simple picture. There are three features (A, B, C), each line shows a possible order of completion. Let's insert a dependency: A must be completed before B. With (A before B), the sequences in lines 3, 4, 6 are no longer possible.

The one dependency (A before B) halves the number of possibilities!

I omit the formula of the calculation, which gives mathematical derivation for three entities:

| Number of dependencies | Options in the sequence |

| 0 | 100% |

| 1 | 50% |

| 2 | 16.667% |

| 3 | 4.167% |

| 4 | 0.833% |

| 5 | 0.278% |

Awesome, isn't it? It also has a positive aspect: just reducing the number of dependencies from five to four increases the degree of freedom by a factor of about three!

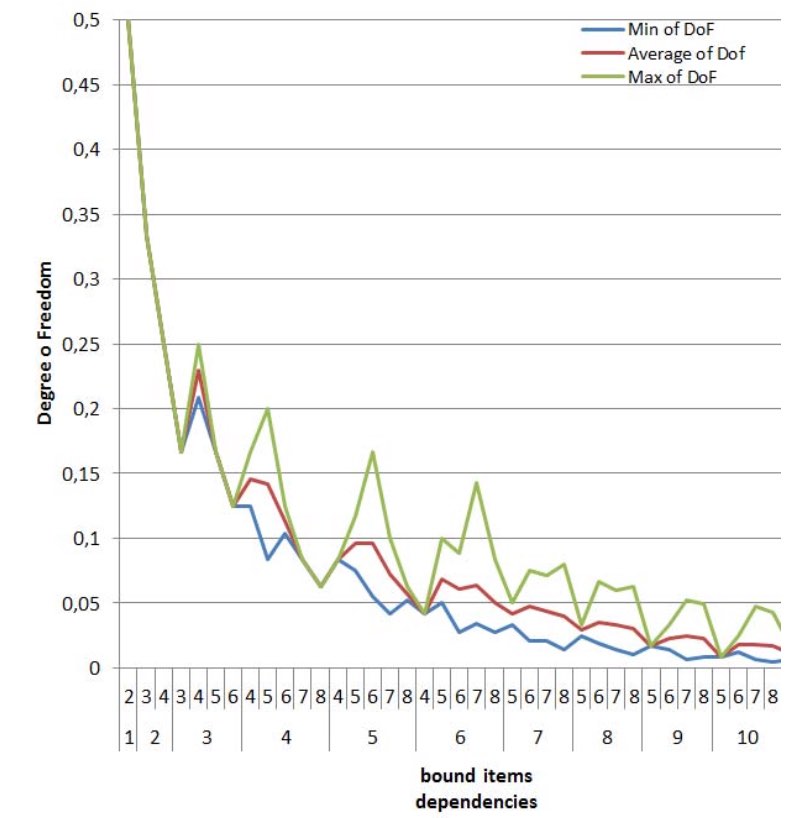

Let's look at this again in a realistic set, a backlog of eight items. This is a number of stories in a sprint backlog that is well within the normal range for a team.

With ten dependencies across all eight backlog items (data point on the far right), there is almost no degree of freedom left in the implementation!

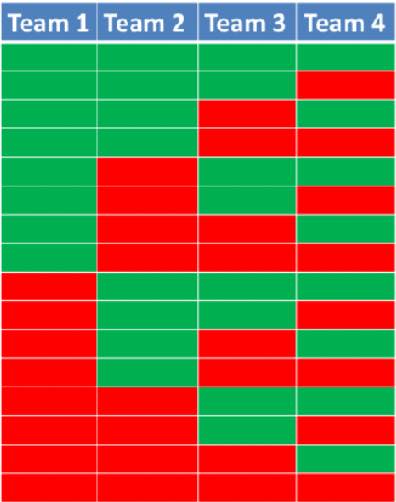

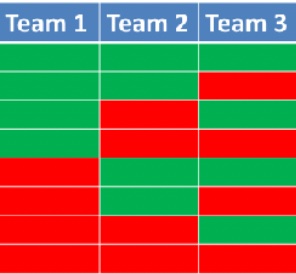

What does it look like when several teams work together? Let's take a look at the picture:

All four teams have dependencies here. Of all the possible sequences, only the first line is possible. This leaves exactly one of 16 possibilities. The probability of a smooth delivery drops to 6.25% (f=1/2^4=1/16)

If it were possible to remove a team from this dependency, the picture would look twice as good:

Exactly one out of eight possibilities offers a smooth delivery, the probability is 12.5%. Note: One of four teams that is not dependent on the others doubles the probability of the other three being able to deliver smoothly! Plus, the independent team itself has 100% of the options!

Why SOLID is still solid

So now it is clear that dependencies should be avoided as early as possible. Solving, ignoring, coordinating - that comes afterwards.

SOLID is an acronym that makes use of mnemonics; it represents the first words of the following five principles for object-oriented programming. SOLID can also be used to understand the basic tricks for avoiding dependencies. As a container for work, I choose a story, which is ultimately just a term to describe a package of actions.

- Single Responsibility Principle: Design the story in such a way that a change to the story does not affect other stories. So if adjustments are necessary in one story, other stories should not be affected.

- Open Closed Principle: Your development should be open for extensions but closed against modifications. This is basically the idea behind increments. You can build on the story without having to change the story.

- Liskov Substitution Principle: If a story refers to one that was completed earlier, it is not decisive for its functioning whether the original story refers to others again. This means in particular: If an earlier story is replaced, the subsequent story must function as a substitute. This principle builds on the first two.

- Interface Segregation Principle: Cut stories so that they are as specific as possible. Generic stories would always have more references because specific ones access them. In the event of future changes, all generic stories and the specific stories associated with them would then always have to be changed. Instead, decoupled stories can be more easily adapted to future technical developments or replaced.

- Dependency Inversion Principle: Completely decoupled stories are not always possible. If a coupling makes sense because many conditions for other stories are explained with one story, then at least this generic story should not be dependent on others, but the details should always be dependent on this abstraction.

The whole thing goes back to (relatively) ancient programming rules. To the principles of object-oriented design, to be more precise. Good old Uncle Bob invented it. A brief digression: Uncle Bob's real name is Robert Cecil Martin and Anyone who reads the Agile Manifesto morning and night will know that this same Robert C. Martin was also involved!

Slicing is half the battle, splitting is the other half!

Right, now back to practice. All five principles can be summarized in one picture. Stories should be sliced in such a way that each of them provides a complete picture of the architecture/through the customer path - described in the picture as "vertical slices".

How does that work? There are two approaches. One heavy and one heavier.

Let's start with the more difficult approach: if the architecture is based on the five SOLID principles, then future developments will be easier. However, this often requires a historical architecture to be adapted. This requires technological, technical and procedural knowledge.

The hard approach is to cut planned stories so that they are independent. There is this one image that I bring up in every training and coaching session with product owners. Even after years of creating stories myself, it remains difficult. At the same time, this image is always helpful!

It's explained quite simply: start with step one, then two, then three. The last two steps are iterative.

What else would help you?

The article is already quite long and perhaps intensive. But the topic has not yet been exhausted. I haven't even written about how dependencies can be avoided or resolved organizationally. Or about how they can be coordinated.

I would write a second part on the subject, I just want to know: What else would help you?

Write a comment