How can strategic, tactical and operational levels be brought together?

In order to create this end-to-end agility, one prerequisite must be met: a shared understanding of the strategy and those parameters that can be used to determine whether the strategic approach is successful on the market or not and to what extent the goals have been achieved or are still achievable. This understanding can only be achieved through regular communication between the management responsible for the strategy and the employees of the implementing units. The concept of "flight levels" has proven its worth for the understanding and interaction of the individual management levels in a company [see Leopold 2016 and Leopold 2018] 1, 2

What are flight levels?

Only certain sections of the overall reality are visible at the individual levels of an organization. It's like flying: a passenger plane flies very high and the passengers have a view over hundreds of square kilometers - although they can see different areas such as forests, farmland and cities, they cannot identify what is happening on the ground. On the other hand, they can cover long distances very quickly. A police helicopter, on the other hand, flies very low so that the crew can recognize details, for example in road traffic. The different flight altitudes therefore each have a different purpose: while passenger aircraft focus on reaching a specific destination quickly and thus on long-range vision, helicopters carry out missions close to the ground, which usually require a quick response.

Organizations function in a similar way: top management must maintain an overview of the interrelationships within the company and developments on the market in order to be able to plan strategically - i.e. with a longer time horizon - set priorities and align the organization accordingly. At the operational level, on the other hand, the day-to-day work is carried out and there is more direct contact with the customer. There are usually dependencies between the individual operational units that need to be coordinated so that the value stream from the development of a product or service to its impact on the customer is as consistent and optimized as possible.

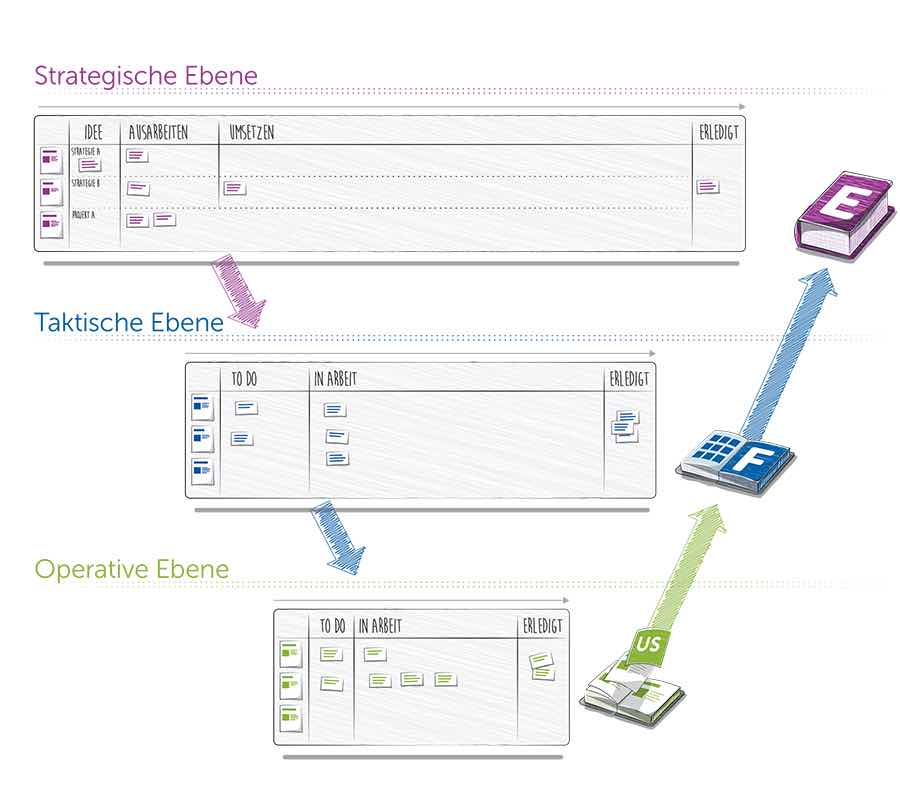

Leopold therefore distinguishes between three flight levels:

- Flight Level 1 - operational level (deliver)

- Flight Level 2 - coordination/operational portfolio management (coordinate)

- Flight Level 3 - strategic portfolio management (prioritize)

These levels are not hierarchical, but task-related. All three levels are equally important for the successful management of a company. Each flight level should work with the visualization of value streams and dependencies, WIP limits and regular meetings (stand-ups and retrospectives), and there should also be a regular top-down and bottom-up exchange (e.g. by team representatives) between the three flight levels.

Once the different value streams in a company have been identified, the Kanban as a method for managing not only production and development processes, but also the portfolio. Before a "Company Kanban", the people involved at the different flight levels of the organization meet in manageable cycles to analyse the current situation, select and prioritize initiatives. The Company Kanban Board serves as a tool that creates transparency about current and planned projects, their goals, key performance indicators, throughput, limitations and obstacles.

A Company Kanban:

- maps the value stream (or value streams) and the individual processing steps across the entire company,

- is used to control the overall throughput,

- uncovers bottlenecks.

If there are several value streams or products that are interdependent in terms of content or the resources used, this holistic view can provide the necessary transparency. The level of detail of the information on the shared board depends on the context of the company and the group working with it.

The task of the strategic level (Flight Level 3) is to collect and evaluate ideas and compare them with the existing capacities of the other levels. This also results in the section depicted on the specific board: top management, for example, uses a board that depicts epics and the next features. Once it has been jointly clarified at Flight Level 3 which next steps should be taken to implement the strategy, the tactical and operational units adopt the topics from the cross-level planning for implementation. According to the principles of lean management, on which Kanban is based, this should be done by a pull instead of a push, i.e. the tasks are "pulled" into processing by the relevant teams based on their available capacities and workload. A request usually passes through several levels (see Part 3). As soon as work packages are completed at the operational level, they can in turn be aggregated into higher-level benefit packages - often called "features" - and thus contribute to the strategic goals.

Visualization of transfer points reduces transaction costs

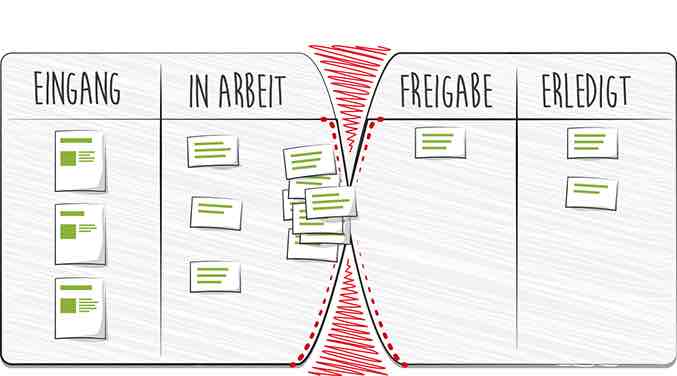

The scope or length of a company kanban depends on the complexity of the value stream, as a new column is created with each handover within a value stream. Theoretically, there are at least three columns (To do - In progress - Done), but in practice the value stream is structured differently in each company and is usually much more detailed (the more precisely a value stream is represented, the easier it is to identify bottlenecks and opportunities for improvement). Depending on the structure, a wide variety of information can be mapped:

- Maturity level of topics

- Sorting (priority) of the topics in relation to each other

- Free resources or queues in the operational implementation

- Allocation of ideas to dedicated units

- Minimum Viable Products (MVPs) for the individual epics

The complexity of the board results from the amount of information required.

When "building" a company kanban, you should therefore ask yourself how a value stream is organized: How many organizational units - departments or teams - must a product pass through before an idea is fully implemented? Such company kanbans should therefore not be "designed" in isolation by a single person and they should not depict a desired process, but rather the process that is actually lived. Furthermore, there are no "finished" boards; rather, they should evolve with each new insight. Presenting the facts on the board and discussing them can always lead to small changes in the processes. Both the board and the teams therefore gain maturity by working with it.

Agile companies try to keep the number of handovers as low as possible in order to keep the effectiveness of the teams and therefore the entire organization high. However, the agile principle of empowerment must also come into play at team level: It not only means that decisions are made decentrally in the teams, but that the teams should be able to develop a product from the idea to delivery to the customer. From a systemic perspective, the presentation of the work steps at team level illustrates how well an organization can apply this principle. The basic principle here is that transitions increase complexity and therefore transaction costs. The rule of thumb is: the fewer handovers there are between different teams, the lower the transaction costs and the more ownership individuals and teams assume for the developed products.

Throughput control - a prerequisite for fast time-to-market

A Company Kanban should demonstrate,

- how much of what was originally started was actually completed;

- how far individual topics have progressed and

- how many topics can be processed in parallel, or in other words: how focused the priorities can be.

When used correctly, the board provides information or key figures that can be used to manage the company. In other words, it provides management with a valid basis for decision-making, makes the achievement of objectives transparent and serves as a basis for joint planning across all levels. Even at the strategic level, management can influence how quickly new products and services (can) be launched on the market - the aim is to optimize throughput.

A Company Kanban not only shows the Chief Product Owner, Lean Portfolio Management or CxO - the titles of the most senior product manager vary from organization to organization - the current status of product development. His process counterpart - often called Chief Scrum Master or Agility Master - also gets an impression of the entire value creation process, its inherent complexities and bottlenecks through a well-maintained Company Kanban. It therefore serves as a starting point for the continuous improvement of the process.

What is important when optimizing throughput?

In this context, throughput describes the performance of the organization. In principle, bottlenecks limit the entire system from strategic planning to operational implementation in equal measure, i.e. there are always restrictions in a value stream that hinder rapid throughput. Better throughput - the faster passage of work through the value stream - can be achieved if the work in progress (or process; WIP) is limited. The WIP indicates how much work is currently in a system. The more work there is in a system, the later work is completed, because in most cases there is constant switching between tasks and the bottlenecks are also overloaded. Many improvement measures are aimed at optimizing the people doing the work - but in fact, the primary goal should be to regulate the inflow of work into a system.

The key to this is limitation: in view of limited resources, it should be possible to complete work or tasks before starting new ones. This not only applies to operational implementation, but also starts with the ideas for projects: A wise selection of projects to be implemented must be made at portfolio level - i.e. the number of projects in the organization is limited. No more projects are started than the existing teams can handle with their current capacities and workloads. WIP limits at the operational levels of a company cannot absorb the load caused by too many initiatives being launched.

This post is part of the Agile Portfolio Management series. The first post in this series is here -> Agile portfolio management

Continue in the next post -> Prioritization and cost of delay

Note: This text is an article by Sebastian Schneider and Lothar Fischmannwhich we published on our website in 2018. As this topic is still very popular, we republished this article on our blog when we restructured our website.

——————–

1 Leopold, Klaus (2016): Kanban in practice. From team focus to value creation. Carl Hanser Publishing House

2 Leopold, Klaus (2018): Rethinking agility: Why agile teams have nothing to do with business agility. LEANability GmbH

Write a comment