Approaches to testing agile organizations

Agility has been on the rise in many companies for years. And while agility was originally applied in small teams, these agile teams are now increasingly being combined into larger (scaled) units. Large-scale projects with several hundred employees are now organized in an agile manner and entire companies are also transforming themselves and creating agile forms of organization. But what does this mean for internal audits? According to the authors, new ways of thinking and working are required, which auditors must understand in order to be able to contribute to the success of the company in this environment. Although the article primarily deals with auditing scaled agile systems, it also offers an outlook on the role of auditing in an agile corporate environment.

Disclaimer: This article is quite long. If you would prefer to read it as a PDF or print it out, click here:

1. challenges for the audit

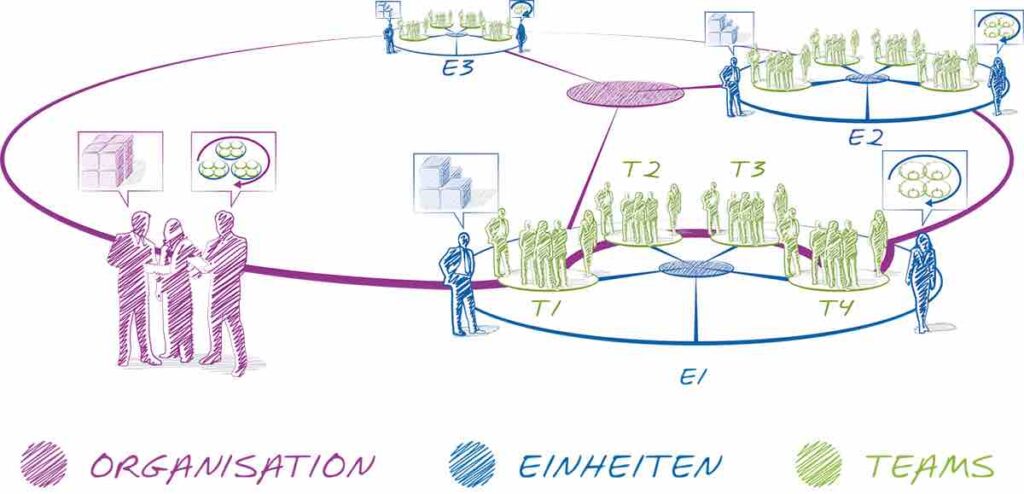

In agile project management, there are now various proven approaches to scaling individual agile teams into larger, cohesive agile units. This results in agile organizations, which can be large projects as well as line organization forms and even entire companies.

These agile organizations pose new challenges for auditing because roles and responsibilities are distributed differently and plans and documents are created dynamically. Familiar audit approaches no longer fit. New audit approaches are required. Static audit procedures will most likely no longer exist in the dynamic audit area because the agile frameworks used will regularly undergo adjustments in practice. Especially since the introduction of agile working methods often involves the implementation of company-specific and interim solutions as part of the transformation process towards an agile organization. This in turn presents internal audit with the challenge of finding individual solutions. Four approaches that can help to respond to this challenge are presented below:

- Flight levels according to Leopold - looking beyond team boundaries & making dependencies visible (chapter 3.1)

- The project cube - auditing agile organizations according to DIIR Standard No. 4 (Chapter 3.2)

- SAFe metrics and self-assessments - examples of internal controls (section 3.3)

- Principles - Agile principles as an aid in the audit (chapter 3.4)

These four approaches are then supplemented by three in-depth topics relating to particularly risky issues. First, however, a brief overview of known frameworks for agile organizations is presented to provide a common understanding.

An understanding of these frameworks also requires a basic understanding of agile working methods. For interested auditors who require further information, we recommend the article "Auditing agile projects" (Andelfinger et al. (2016)), which, as a predecessor to this article, provides auditors with an overview of agile ways of thinking and working.

2. frameworks for agile organizations

Two well-known frameworks for agile organizations are Large Scale Scrum (LeSS) and the Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe).

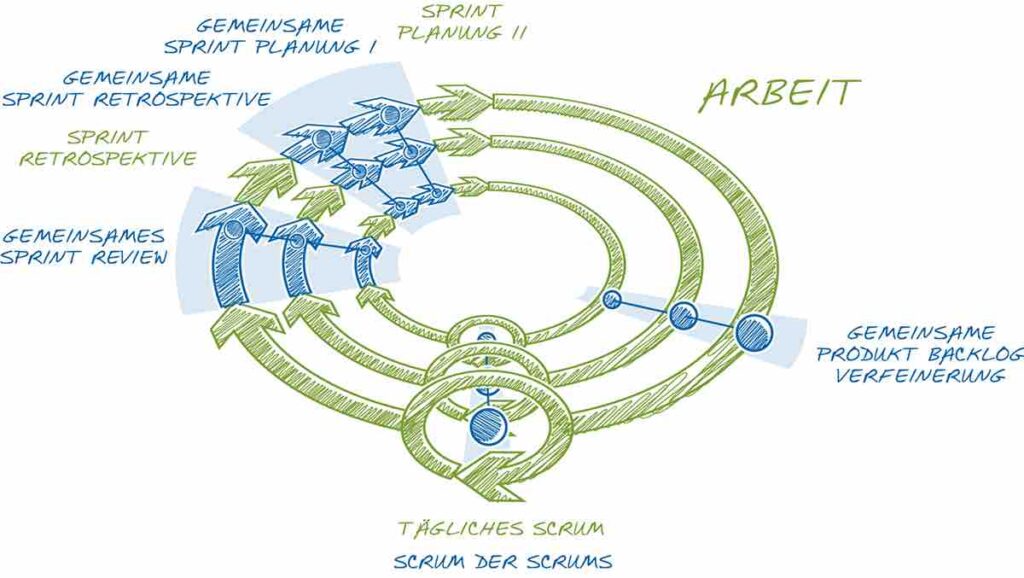

2.1 What is LeSS

Large Scale Scrum (LeSS) offers a consistent agile solution based on Scrum for working together with several Scrum teams on a joint product - especially for large projects or complex products (for more on LeSS, see Larman/Vodde (2016)). The LeSS approach is to keep the Scrum sprint cycle, but to carry out certain Scrum events together. With LeSS, Sprint Planning One and the Sprint Review are carried out jointly. Each team has its own retrospective and there is also a joint retrospective with representatives from all teams. For horizontal coordination, there are joint product backlog refinements and inter-team coordination (e.g. Scrum of Scrums).

The audit of large-scale LeSS projects is based on the procedure for Scrum projects. The additions and extensions to Scrum projects must be taken into account accordingly when planning the audit. This audit procedure for agile projects has already been described in detail in Andelfinger et al. (2016).

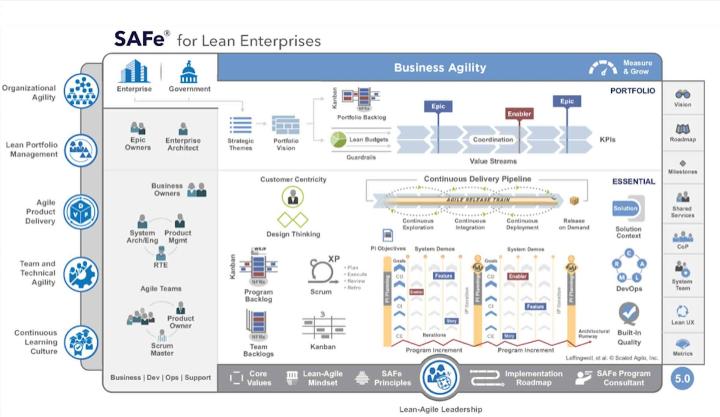

2.2 What is SAFe?

The Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe) is - alongside LeSS - one of the most widely used frameworks for scaling agile product development with many teams (for more on SAFe, see Knaster/Leffingwell (2020)). SAFe builds on lean management and provides an agile framework for the team level, the programme level and the entire organization (portfolio level).

The reasons for the popularity of SAFe are:

- Large project organizations can be combined in an agile organization.

- The program and portfolio levels are integrated into this.

- Standardized techniques, roles, meetings and artefacts are made available.

Agile Release Trains (ART) are at the heart of the framework. Several teams work together in an ART and work on a joint product. A large company typically budgets several such products in a portfolio in order to optimize the use of resources in the development of many complex products across the board. The definitions and differences between portfolios, programs and projects are described in DIIR Standard No. 4, among others.

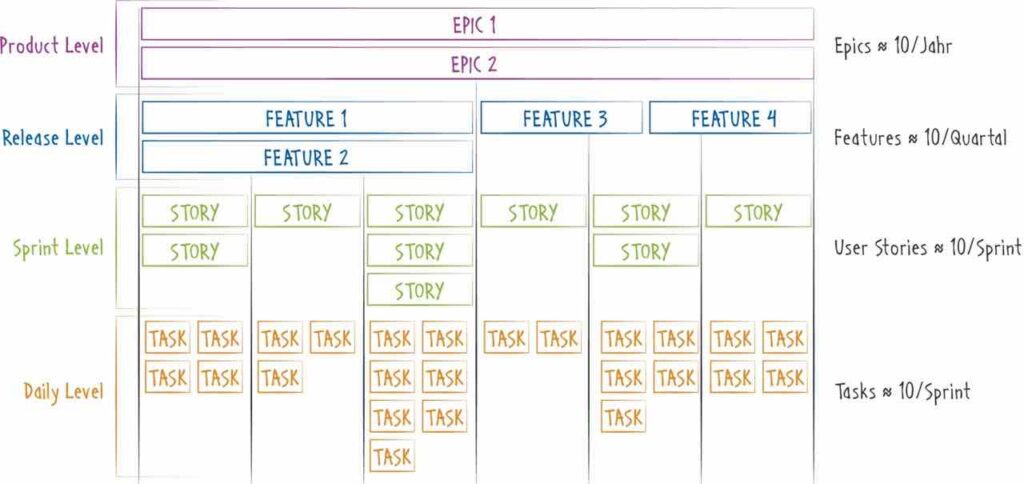

To scale agile teams into an entire agile organization, the planning horizon at the higher levels is extended from two to four weeks (agile teams) to several months or even years.

Stages of two to three months are then planned at ART (unit level). A further level above this comprises several agile units that are managed in a portfolio backlog with an organization of several units and are strategically aligned for one to two years. This means that features and epics are added to the basic agile planning units - user story and tasks - when scaling agile projects.

In the SAFe framework, the collaboration of many development teams is implemented accordingly in the planning levels Essential (units or ARTs), Large Solution (solution development consisting of several units or ARTs) and Portfolio.

The various elements of SAFe are presented in the big picture of the SAFe organization:

SAFe is constantly being further developed and, with SAFe 5.0, currently offers the most comprehensive framework for agile organizations. A large organization with many agile teams poses a particular challenge in terms of its complexity.

3. the audit of agile organizations

Due to the large number of ways in which agile organizations can be implemented, there cannot be a single audit for agile organizations. Auditors will have to use a risk-oriented approach to find an individual way of identifying and auditing the relevant risks. Such a risk could exist in a product that is created by a single agile team because the product has a high regulatory significance. But it could also be the overall budget for a portfolio because the investment has a high significance for the company. But it will certainly also be relevant to check whether agile organizations apply appropriate and effective processes to implement the underlying vision. In the following, four audit approaches are presented that can be used and combined to develop your own concrete procedures for auditing agile organizations.

3.1 Flight level according to Leopold - looking beyond team boundaries & making dependencies visible

Even with simpler frameworks such as LeSS, but even more so when looking at the big picture of the SAFe framework, the high level of complexity and the multitude of topics and responsibilities that need to be taken into account by the auditors during audits quickly becomes clear.

In line with Leopold/Kaltenecker (2018), we therefore suggest using the model of the three flight levels as an orientation aid to clearly structure the complexity of agile organizations and thus make it easier to test. According to Leopold, the 3 flight levels are a "simple thinking model" and communication tool for organizations to reflect on: "Where in the company is the right lever that we want to pull in order to improve the company's business agility and steer it in the desired direction on the market?" (Leopold 2019).

The three flight levels according to Leopold/Kaltenecker (2018) are defined as follows:

Flight level 1 - Operational level:

Flight level 1 is about working professionally at the operational team level. The focus is local and the coordination and synchronization issues that are important for scaling from a global (value creation) perspective are not necessarily considered.

Flight level 2 - coordination level:

Flight level 2 is about keeping an eye on and optimizing the interaction between the teams from the perspective of the entire value chain so that the teams work on the right things at the right time (Leopold, p. 26). Instead of a team-related local optimization, Flight Level 2 is about achieving a global (value chain-oriented) optimization of the entire agile system or an entire agile project (across teams).

Flightlevel 3 - Strategic Portfolio Management:

Flight level 3 is about ensuring the connection of agile projects and programs to the overall portfolio management and achieving a 'smart selection and combination of projects and strategic initiatives, as well as optimizing the flow through the value chain(s) given the actual resources available' (Leopold, book Kanban 2, p. 32).

The leverage effect for value creation increases from flight level to flight level, while the level of detail decreases. Overall, they help to keep an eye on three key success factors in agile organizations: Team excellence (level 1), cross-team value stream optimization (level 2) and (market)-strategic portfolio management (level 3).

The three flight levels can now be used to derive important suggestions for auditing and reviewing agile organizations.

Examination suggestions for Flightlevel 1 - Local team perspective:

The focus of Flight Level 1 is on the professional implementation of elementary agile methods such as SCRUM, on team excellence and on achieving a constant flow of work within the team. For Flight Level 1 audits, we recommend the aforementioned article "Revision of agile projects" (Andelfinger et al. (2016)) and DIIR Audit Standard No. 4 (DIIR (2019).

Examination suggestions for Flight Level 2 - Cross-team coordination:

The collaboration of several teams in agile organizations leads to new challenges. Therefore, comprehensive coordination is necessary for an optimal value stream. The aim of this coordination is to optimize the value stream across the board. This is ensured by appropriate coordination tasks, coordination roles and forms of interaction. Local optimization of individual high-performance teams tends to be counterproductive.

Exam questions and topics can be:

- Is there an appropriate cross-team prioritization of tasks?

- What waiting times or bottlenecks are there at the team interfaces or in the value stream?

- Are the iteration cycles long enough to generate substantial increments, but also short enough to allow appropriate feedback and learning cycles?

- Is there ongoing optimization of the workflow across the entire value stream?

- Is the value stream and the work taking place within it visualized?

- Are roles for cross-team synchronization and coordination filled and exercised effectively?

Examination suggestions for Flightlevel 3 - Strategic Portfolio Management:

A central goal of agile organizations is to work on the right products from the perspective of the overall organization. This means that a connection to the strategy and portfolio management is important - as is an 'agile' ability to react if, for example, a new prioritization of the portfolio is necessary due to changes in the market or technology. This is the only way to ensure the ongoing optimization of value creation for the entire organization.

Exam questions and topics can be:

- Is there an appropriate strategy? Is it being implemented effectively?

- What objectives and expectations have been formulated for strategic projects?

- How is feedback on the implementation status and success measured?

- How are the strategy and portfolio updated?

- Is the strategy adapted to changing conditions?

Examination suggestions for the interaction between the flight levels:

The three flight levels help to map the complexity of agile organizations on three levels (operational team excellence, coordination, strategic portfolio management). However, it is of central importance for the effectiveness of the approach that there is also appropriate interaction and communication between the flight levels. Leopold (2019) therefore also refers to these two tasks as the 'tactical component', which should definitely also be considered across all levels. According to Leopold, agile organizations are about agile management of the specific levels from the perspective of the overarching strategy in order to ultimately optimize organization-wide value creation and avoid local optimizations. In other words: the outcome (in the sense of value-creating results) should be optimized instead of a mere output orientation (any result - and as much of it as possible).

This goal can only be achieved if the three flight levels are linked in an appropriate manner (i.e. via suitable processes, roles and committees). This also includes spatial structures (buildings, rooms and technical/organizational facilities) and communication tools.

Exam questions and topics can be:

- Examination of agile organizations along the three flight levels with regard to possible communication, coordination and competence risks between the individual levels

- Are the spatial structures/communication tools suitable for meeting communication needs?

- Evaluation of identified interaction and communication deficits and derivation or agreement of targeted measures to eliminate them.

Exam tip:

One risk of agile organizations is that the teams are not cross-functionally staffed and do not independently deliver value-creating increments, but instead continue to reflect the (classic) functional structure. Here, an examination of the dependencies of the teams and the measures to reduce these dependencies is an important contribution to the success of an agile organization.

3.2 The project cube - auditing agile organizations according to DIIR Standard No. 4

In order to carry out an audit of a project, the professional association for internal auditing "Deutsches Institut für Interne Revisionen e. V." (DIIR) recommends the application of its Auditing Standard No. 4 "Audit of Projects by Internal Audit" (DIIR (2019)).

The project cube introduced in this standard provides orientation when reviewing projects:

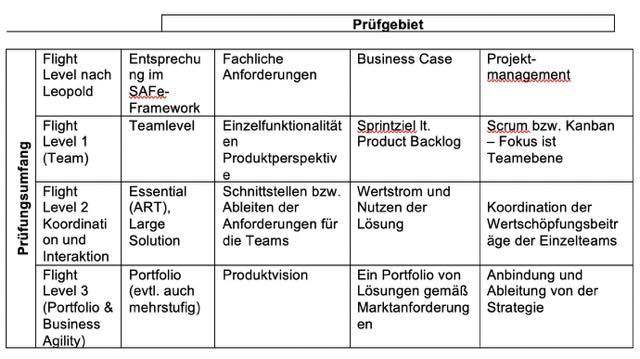

This cube is particularly helpful when planning an audit for the appropriate adjustment of the audit scope, audit area and audit objective. For a structured approach to agile organizations, it can help to adapt this cube. Here, the Fligthlevel model can be integrated into the audit scope dimension:

Certainly, not all audit objectives for audit areas will be equally pronounced in the levels of the audit scope. It is therefore important for the audit of agile organizations to ensure that it is clear which audit scope is to be considered. For example, the topic of compliance with development guidelines is generally more relevant at flight level 1. SAFe users can also assign the SAFe levels to the flight levels (see column 2).

This view becomes clearer if the dimensions of audit scope and audit area are summarized in a matrix and specific audit objects/audit items are assigned:

Exam tip:

A coordinated audit at all three levels with targeted risk-oriented audit procedures certainly has the greatest impact, as all levels interact with each other.

3.3 SAFe metrics and self-assessments - examples of internal controls

Agile organizations should be characterized by integrated controls that ensure that the system does what is intended. The SAFe framework also recommends metrics for this at various levels, such as test coverage, number of defects detected, etc. These metrics offer two approaches for testing. On the one hand, it should be checked whether the metrics have been collected correctly and whether the results are being responded to effectively. On the other hand, it is worth taking a look at metrics as part of a risk analysis by the audit, as weaknesses can be identified and causes can be made transparent through audits.

The SAFe framework offers thematic self-assessments that are very well suited for use in audits. Even for audits of agile organizations that are not based on the SAFe framework, it is worth taking a look at these self-assessments because they contain a large number of questions that can serve as impulses for audits.

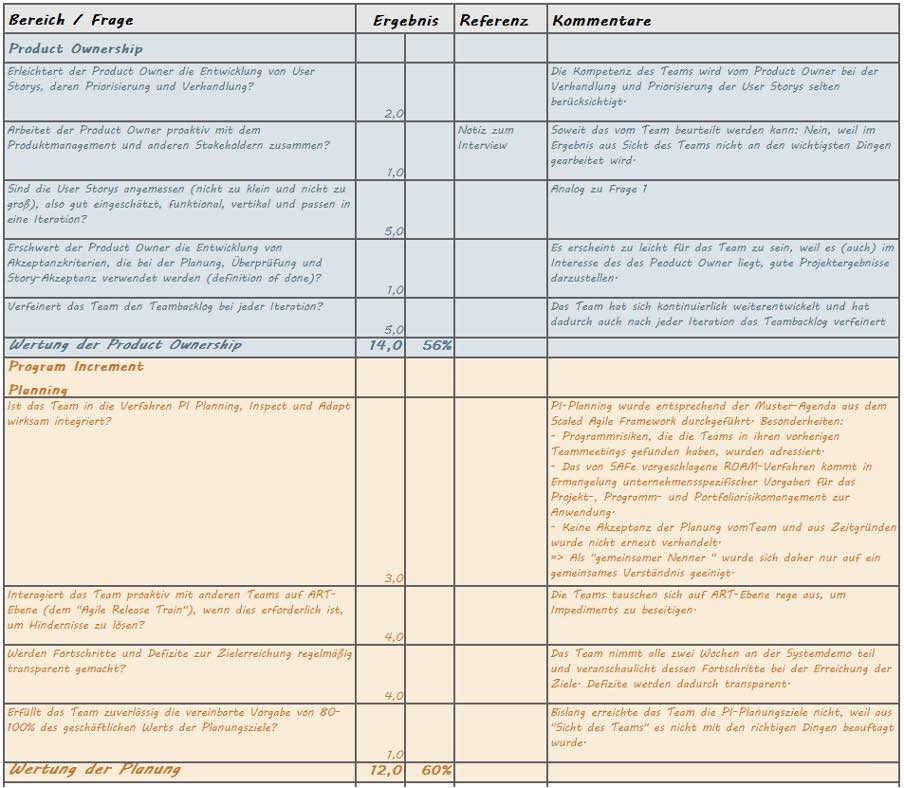

Example: Team self-assessment

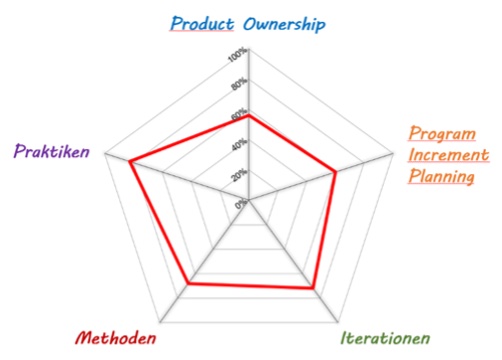

The following radar chart shows an example of an evaluation of team practices. This highlights the relative strengths and weaknesses of a team.

The radar chart shown is automatically generated on the basis of the respective assessments

(rating: 0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = occasionally, 3 = often, 4 = very often, 5 = always)

for the questions and can thus be easily exported to an audit report.

If the team assessments are used consistently for each iteration (sprint), the effectiveness of the improvement measures taken can also be evaluated and tracked over time in the case of recurring use.

The checklists for the team assessment and other topics, such as

- Agile Product Delivery Assessment

- Enterprise Solution Delivery Assessment

- Lean portfolio management assessment

- Lean-Agile-Leadership-Assessment

- Organizational Agility Assessment

are published by the organization "Scaled Agile Inc." on their homepage (in English) with formulas for evaluation and graphical representation of the radar diagrams for download at the address https://www.scaledagileframework.com/measure-and-grow/ made available.

Exam tip:

When auditing organizations based on the SAFe framework, it must be checked whether these assessments are carried out or evaluated by the audit department. Alternatively, it should be assessed whether the self-assessments have already been used by the teams or the 2nd line within the project. If these assessments have been carried out as self-assessments, it must be taken into account that those involved regularly assess themselves better than an uninvolved third party would. A review by Internal Audit can help to calibrate this self-assessment system.

- SAFe principles - Agile principles as an aid in the audit

Since the publication of the agile manifesto, principles have been of great importance in agile frameworks. They represent a kind of guideline for shaping collaboration and adapting the frameworks to the company's needs. It is therefore important for auditors to be familiar with these principles. The principles can also be used as a basis for the audit. Using interviews to ask how the principles are actually implemented can help to identify weaknesses. For example, SAFe 5.0 formulates ten principles that are explained in detail in the framework:

- Adopting an economic perspective

- Apply systems thinking

- Embrace variability; have alternatives ready

- Incremental approach with fast, integrated learning cycles

- Set milestones based on objective evaluation of functioning systems

- Visualize and limit work in progress, reduce batch sizes and manage queue lengths

- Use cadences and synchronize with cross-domain planning

- Igniting the intrinsic motivation of knowledge workers

- Decentralize decisions

- Organize with the value as the center

Exam tip:

These principles are difficult to convey through single sentences or buzzwords. Examiners should develop a deep understanding of what exactly is meant. In addition to studying freely available texts (e.g. https://www.scaledagileframework.com/safe-lean-agile-principles/ ) training on these principles is highly recommended in order to internalize the underlying way of thinking through appropriate exercises and discussions.

- In-depth topics for auditing agile organizations

In addition to the four audit approaches mentioned above, three more in-depth topics are examined in more detail below.

- Project risk management - reviewing its effectiveness in corporate risk management

While in the past (at the beginning of "agility") only small projects (mostly IT projects) were initially carried out using agile procedures, the application quickly developed into ever larger agile organizations (projects, programmes, portfolios and ultimately entire companies). The risks in these organizations are becoming increasingly significant, meaning that consideration must be given to them in corporate risk management (e.g. in accordance with MaRisk, KonTraG, etc.).

Agile frameworks such as Scrum or SAFe stipulate that risks must be taken into account when prioritizing tasks and therefore implicitly include risk management in these procedures. SAFe addresses the topic of risks more explicitly in Program Increment Planning (PI Planning) by using tools (e.g. the ROAM Board) to identify and deal with risks.

Exam tip:

Appropriate and effective risk management is and remains a critical success factor, even for agile organizations. In particular, compliance with internal company or industry-specific regulations must be ensured. This is also important from the perspective of the 3 Lines of Defense model. A lack of or inadequate risk management in an agile organization must inevitably lead to increased auditing activities.

- Business cases - An example for testing support functions in agile organizations

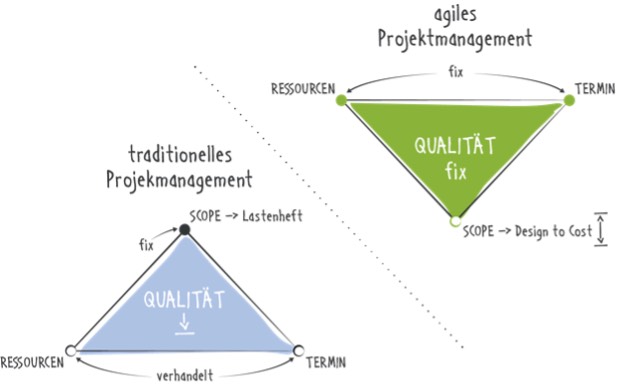

The testing area of the business case in agile organizations differs from the classic project management system in that in classic project management, the scope of the project to be delivered is typically clearly agreed at the beginning and the budget and time are set on this basis. Later on in the project, control is exercised primarily by adjusting resources and/or deadlines to compensate for deficits. In agile project management, the traditional project management triangle is turned on its head.

In agile approaches, on the other hand, the team (resources) and the time structure (sprint length) are fixed. For each sprint or each iteration of programmes and portfolios, the requirements to be implemented next are jointly prioritized again based on the feedback from the developed product. This means that the scope (design to cost) is agreed on a regular basis and is the key to managing agile organizations. This takes place within an agile portfolio as part of an agreed budget in line with a company's strategic planning. While in traditional project management the decision for a project was made on the basis of the business case planned well in advance, in agile organizations in particular the decision is based more on the current needs of the market.

Risk:

Especially in product development, agile working at team level has been spreading for many years. For many other support functions involved within agile organizations, however, agile working is very new. In finance departments, for example, this can lead to attempts being made to support agile developments with traditional tools. Sooner or later, this leads to conflicts.

Exam tip:

The overall system can only work if all units involved pull together. And if the decision has been made for a system to work agilely, supporting functions must also pull together. If you want to orient yourself on the principles mentioned above (section 3.4), you will quickly recognize that the principle of system thinking, among others, comes into play here.

The fear of not fulfilling regulations or audit requirements with new agile working methods is often a reason for not adopting these new working methods. If the audit is able to provide certainty here and point out alternatives, the audit can make a significant contribution to functioning agile organizations.

- Value streams - An orientation aid for auditing

Agile organizations should align and organize themselves according to value streams. A distinction can be made between operational and development value streams.

Operational value streams describe the generation of benefits for the customer. For the organization, these are usually the revenue streams. The portfolio budgets a development value stream that delivers an improvement to the operational value stream. A budget is assigned to each development value stream. Although a series of guard rails define guidelines for their use, they also enable greater autonomy because the effort involved in traditional project-based budgeting is eliminated. The aim is to be able to react more quickly to market requirements (to secure the value stream for the future) while still managing expenditure responsibly.

Exam tip:

The audit should check whether the agile organization has aligned itself with its value streams.

For value stream organizations, audit planning along these value streams makes sense. This is because the activities in the value streams are highly interdependent. A purely project-related audit does not cover all relevant risks.

- What are the requirements for the organization of the audit in agile organizations?

Agile organizations become necessary as soon as several teams work together on a joint product. The complexity increases when several products are also being worked on. In order to do justice to these audit objects, audit execution must also be adapted, as:

- the audit cannot keep pace with agility (the progress of projects) using conventional annual planning.

- it is difficult for a single auditor to have an overview of the entirety of a complex agile scaled system.

- auditors may still lack the experience for agile MindSet and agile methods.

This is where the authors recommend agile auditing or the transformation to agile auditing. Because agile auditing makes it possible:

- Iterative approach to the relevant risks through short audit cycles (sprints) and inherent adjustments to audit plans (reviews)

- Cross-functional agile audit teams and agile audit methods

- Auditors with agile competence with regard to agile methods and agile mindset are perceived as partners by agile auditors.

- Scaled agile auditing - impetus for the further development of auditing work

When audit teams work in an agile manner, the idea of making agile methods and ideas usable for the entire audit department quickly arises. This creates agile organizations in the audit department, i.e. several teams have to be coordinated. Here, the authors would like to provide some brief impulses from the above-mentioned principles (see section 3.3).

- Adopting an economic perspective

For auditing, this means above all deploying audit resources where they will bring the greatest benefit. This principle has been used intensively in auditing work for many years with the risk-oriented approach. - Apply systems thinking

This principle could have an impact on audit planning. While attempts are often made in annual planning to master complexity by auditing the most risky individual elements in order to achieve an improvement for the system as a whole, it is better to think in terms of large units and to audit interrelated systems from end to end (see also section 4.3 on value streams). This could mean not auditing sub-elements of a system every year, but instead focusing on the system as a whole once every several years. - Assume variability; have alternatives ready

For the audit, this principle can mean that a large number of ideas on possible risks and audit procedures should be collected at the start of the audit. During the course of the audit, you will continuously learn about the audit object and can then use these ideas in a more targeted manner. - Incremental approach with fast, integrated learning cycles

The aim here is to use the classic plan-do-check-adjust cycle in the shortest possible time periods. To this end, it makes sense to divide an audit into several cycles in which risks and audit procedures are planned, performed, reviewed and adjusted. This can be done at several levels, e.g. at the level of individual audit procedures, at the level of the entire audit and also at the level of the entire audit. - Set milestones based on objective evaluation of functioning systems

As in waterfall software development, auditing also tends to set milestones for audits such as the creation of an audit program, the start of audit procedures, the writing of reports, coordination, publication, etc. before the start of activities. However, not all the information is available at this stage, so milestones are often missed. The solution is to set milestones at which objective assessments for the next steps are determined. This means that at weekly milestones, the results are reviewed and the next steps for the audit are determined. This logic should be applied at all levels of the audit, i.e. an annual audit plan should also be reviewed at regular milestones, e.g. every two months. - Visualize and limit work in progress, reduce batch sizes and manage queue lengths

This is about using Kanban boards to make it clear to everyone involved where each task stands. And there is something else to this principle: auditors often work on several audit tasks in parallel. Due to the set-up times when switching from one topic to the next, this principle makes it much more sensible for auditors to only work on a few topics at the same time. Different levels can also be relevant here, i.e. boards can be used at audit level, but also across audits for annual plans. - Use cadences and synchronize with cross-domain planning

The aim here is to create a rhythm. At flight level 1, this means that the auditors should have completed audit activities at the same times (e.g. fortnightly). For flight level 2, on the other hand, the teams should be ready at certain synchronization points (e.g. every 2 months). - Sparking the intrinsic motivation of knowledge workers

Auditors are now highly specialized knowledge workers. Also, auditors often work in long exams, the meaning of which is questioned by the auditee and sometimes by the auditor. Intrinsic motivation to develop the skills of employees can best be achieved if the auditors are convinced of the meaning and benefits of the work.

- Decentralize decision-making

Every decision that has to be extended to a higher level of authority leads to a delay. For audits, this has two sides: The auditor should be able to make their own decisions to the greatest extent possible in the audit process, in report writing and in report reconciliation. But this principle is also important for the audited parties. Report reconciliations that are delayed because they have to pass through different hierarchical levels where different positions are represented hinder the rapid rectification of identified deficiencies. To counteract misunderstandings: The centralization of strategic decisions is just as much a part of this principle. Clear criteria as to which decisions should be made centrally or decentrally must be implemented. - Value stream orientation

Just as agile organizations organize themselves around value streams in order to be able to adapt more quickly to market and customer requirements, the audit program should be oriented towards these new value streams in the same step - ideally at the earliest possible stage.

- Conclusion and outlook

The world of work is changing. More so in some sectors of the economy, less so in others. However, any audit organization that experiences this change will quickly realize that new approaches are required. This is where the approaches presented in this article can help to rethink internal auditing in agile organizations:

- The flight altitudes according to Leopold give inspectors the necessary overview.

- The agile project cube provides structure in audit planning.

- SAFe metrics support the audit process.

- The agile principles provide orientation for an audit in an agile environment.

Agility will become even more important in many areas of the economy. This offers many opportunities both in auditing and in audit management. Each audit must decide for itself how it wants to take advantage of these opportunities.

Bibliography:

Andelfinger, U./Battenfeld, J./Binder, J./Hackenholt, A. (2016): Revision of agile projects, Agile projects - understanding and reviewing. In: ZIR, 5/2016, pp. 220-231.

DIIR (2019): DIIR Auditing Standard 4 - Auditing of projects. V3.0 - 2019. Available online at https://www.diir.de/fileadmin/fachwissen/standards/downloads/DIIR_Revisionsstandard__Nr._4_V_3.0_Sept_2019.pdf, last checked on 06.01.2020.

Leopold, K./Kaltenecker, S. (2018): Kanban in IT. Carl Hanser Verlag Munich, 2018.

Knaster, R./Leffingwell, D.: SAFe 5.0 Distilled. Addison-Wesley 2020.

Larman, C./Vodde, B.: Large-Scale Scrum - more with LeSS. Addison-Wesley 2016.

About the author:

Jörg Battenfeld is a change management expert and partner at wibas

More articles in this digital magazine:

Inner growth processes as part of successful transformations

Or: what happens when we solve external structures?

Change initiatives often describe how external structures and processes in organizations should change. It is easy to overlook the fact that external change also requires internal growth. We present two models that offer an introduction to this ...

Agile working and positivity in coaching

Tears of relief and joy at seeing themselves in a positive light and accepting themselves even more for who they are. These were the reactions to our coaching sessions with the Agile Masters. We have married our insights from positive psychology with agile working in coaching. And the reaction of the coachees is confirmation enough that we are on the right track ...

Conjuring up satisfaction - What does it take to make people in organizations feel good?

How are people at wibas doing in lockdown? I conduct a telephone survey and ask "magic wand questions": What does it take for people in organizations to be happy? Looking at the answers leads us on a path to dealing with happiness ...

Write a comment