We are now all working according to SAFe. With our Spotify model, we are ready for the future. With the Scrum of Scrums, we will bring all teams together. We can escalate important decisions up to the Chief Product Owner. Thanks to agile portfolio management, we have all dependencies under control.

Have you ever experienced something like this? Oops. Someone may have skipped the most important rule of agile scaling.

What is agile scaling anyway?

But first things first. Before we get to the most important rule, let's agree on what agile scaling actually means. Let's jump to the end of this explanation: there is no fixed definition.

Even a second glance reveals that agility itself needs a lot of explanation! Some see it as a focus on speed, others on adaptability, still others on flexibility, some even on customer value. What is agility? What purpose does it serve? This question should be asked at the very beginning. Right after the consideration "why does this company exist"?

So let's define it, at least for this article: Agility means the adaptability of the entire organization to the needs of the customer. Careful, it says

- Ability to adapt; not "everything has to change all the time".

- entire organization; not "a lot of units that work agilely".

- Customer needs; not "just do what the customer says".

Good. Done. Next. Scaling. What does that mean? I ask myself the same question. So let's try a friendly approach. Agile working methods are generally based on a decentralized, local design. There is almost always a team as a unit. In a sense, this is the atom of the organization. Just as the atom is the smallest (humanly conceived) unit of a chemical element. Yes, of course, there are even smaller parts, but in terms of chemistry, the atom and in terms of agility, the team are the smallest units.

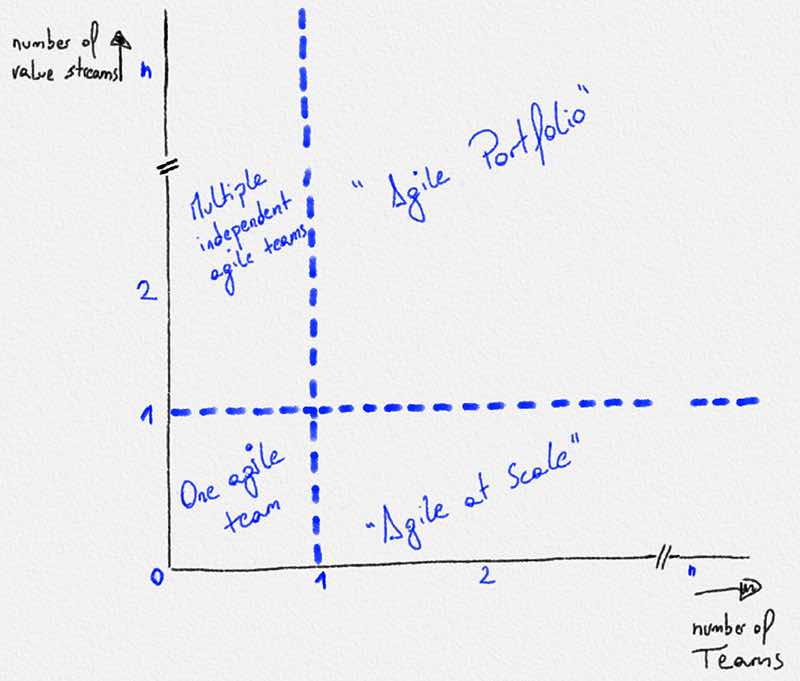

When more than one team is needed to deliver a solution, it is scaled agility. As all the teams involved are working on a solution, sharing in the stream of value creation, they need to coordinate. This includes planning together and processing feedback together. This is much easier in a synchronized cycle.

If there are several value streams (products/solutions) that are largely independent of each other, they do not have to work in a cycle that synchronizes planning, implementation, inspection and adaptation (PDCA cycle). However, there is also little to be said against this apart from having to provide bandwidth and space for the events.

What is an agile framework needed for?

SAFe, LeSS, DaD, SaS, Enterprise Scrum, Nexus... there is a whole range of frameworks that call themselves that. And then there are models that can be found more than once, but are somehow not so suitable for the model of an organization. For example Spotify, Agile Portfolio Management, OKR. Whatever it means to organize according to these. However, I don't want to judge at this point whether and when which one makes sense.

However, I can't resist making a comment: After all, 19% of the answers to the question "which framework does your organization follow to help scale Agile?" in the 15th State of Agile Report are "don't know". I've been wondering for a few years who answers this way and what representativeness this report has, but it's always enough to make me smile when it's scaled and the respondents don't know what kind of idea it is. Not knowing cannot be the reason, that is a separate answer option.

So what is the general advantage of aligning the organization to one of these frameworks?

I can report the following from non-representative accompaniment of decision-makers in companies. A framework provides orientation for processes, responsibilities and artifacts. Frameworks provide patterns to structure complex relationships. They use successful practices, methods and techniques. Frameworks create comparability with other companies that also follow them. Sometimes they even offer patterns for introduction.

So there is a lot to be said for frameworks. Is there also something against it?

One argument that I come across in articles, presentations and conversations is that companies can no longer have a competitive advantage if they organize themselves according to the same framework.

However, this argument that the organization is the same with the same framework does not apply to any framework that I know of.

An important distinction needs to be made here. It is a framework, not a blueprint or a model. It is not simply a transfer. Anyone who does try it will quickly realize that it doesn't work. Too much has to be adapted to the specific organization. First of all, it is important to understand what the organization's products actually are. Here is an earlier article that explains how products can be defined.

And then to analyze how value creation happens. Here is a previous article that explains Value Stream Identification.

Subsequently identify where waste regularly occurs and where bottlenecks are.

Unfortunately, frameworks seem to tempt some decision-makers to think hastily in terms of solutions.

Solutions that are too simple are problematic

Companies are complex. They are complex because at no point in time can all processes be determined in such a way that future events can be predicted with certainty. Similar to weather forecasts. Tomorrow's weather can be predicted with a certain degree of probability, but the more turbulent it is, the more difficult it is. Predicting the weather in four weeks' time, on the other hand, is hardly possible. Perhaps artificial intelligence will change this. Both for the weather and for the organization.

To be able to deal with this complexity, organizations themselves must be complex. A solution that is less complex than the environment in which it is applied will not meet the challenges. It's not just me. There is a rule called Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety. This states that organisms must be able to react appropriately to all stimuli in order to survive as a species in the long term. They therefore require the necessary diversity for these stimuli. W. Ross Ashby contributed knowledge from the fields of zoology, biochemistry, medicine and mathematics - he was a self-taught universal scientist. Ideal prerequisites for helping to shape the scientific field of cybernetics in the 1950s.

Why is this rule of necessary diversity important?

Simply imposing an agile framework does not do justice to the complexity in which companies operate.

And if it is attempted, then the framework only applies superficially. But in order to meet all the challenges, people are literally forced to find their own ways to simply "deliver". Pretty soon, the new agile framework is a façade behind which people look for their own ways of working.

And then the necessary complexity is greater than necessary. The organization is more complex than it needs to be. Why is clear: the rules from the framework apply and practices exist/emerge in the background to "get things done" anyway. People are extremely self-organized and find their own way. Unfortunately, agile scaling has achieved exactly the opposite of what was intended.

The most important rule of scaling is...

...not to scale.

The most important and very first consideration should be: How can I simplify the existing organization?

How can value creation be organized in such a way that units that are as small and independent of each other as possible work as autonomously as possible?

The greater the organizational freedom of each unit, the greater its ability to adapt. The unit can then work more intensively with the respective stakeholders. And yet the agility of the entire organization increases because the units do not influence each other at best.

In software, this idea has been the guiding principle for the implementation of new architectures for a few years now. Software solutions with modules consisting of parts that can be integrated into one another are simply more adaptable to future developments. Of course, this requires interfaces that connect these units. However, agile frameworks provide suitable processes for this.

Before deciding to introduce scaled agility or an agile portfolio, the existing organization should be simplified. The organization must be "descaled" to a certain extent.

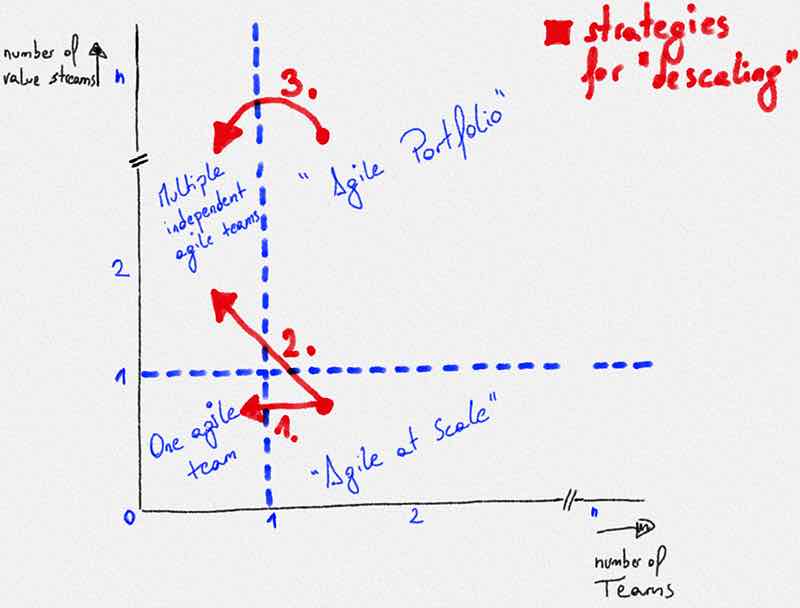

Strategies for "de-escalation"

1. reduce

Can the same work be done by fewer people?

Bill Gates is quoted as saying:

"A great lathe operator commands several times the wages of an average lathe operator, but a great writer of software code is worth 10,000 times the price of an average software writer."

A small unit of excellent people working together can achieve more than if they are spread across a larger organization and then adapt to the average performance. Reed Hastings and Erin Schmidt describe in their book (see below in the prize draw) how Netflix has gradually developed a high-performance culture with few rules.

2. design independently

Can the flow of value creation be changed in such a way that independent units become possible?

The second strategy builds on the first. If one small unit creates excellence, how much could many small units create? Units that need little coordination because they have the technology and organization to ensure that results can be integrated. At this point, it is important to make a distinction: the internal organization and the products perceived by customers are two different things. In this article, I go into this in much greater depth. Yes, this strategy means defining more value streams. But if these have less to coordinate externally in total, the organizational complexity decreases in comparison to a large value stream with more coordination "internally".

3. decentralization

Can a portfolio be decentralized?

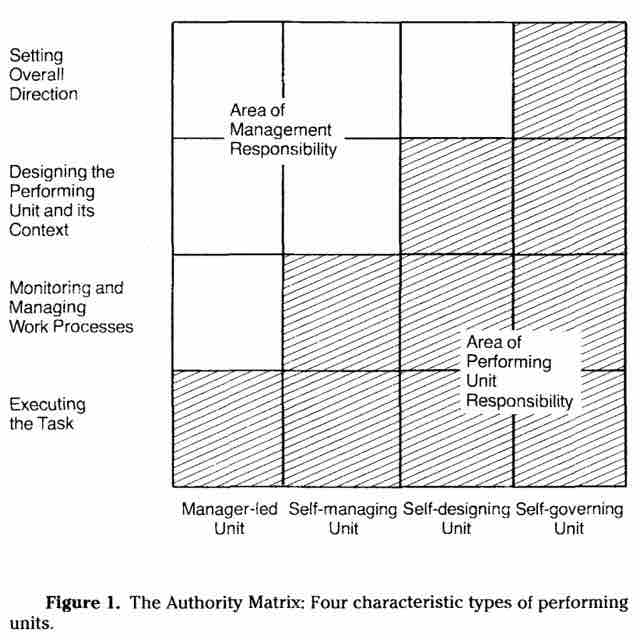

The third strategy builds on the second. If decentralized decisions are "better" than centralized ones, then there is no need for portfolio management. The responsibility for improving the value stream then lies with each unit itself. Richard Hackman refers to these units as "self-designing units". In his milestone article, he refers to teams - without describing them exactly - but the logic can be transferred. Self-design can certainly take place with centrally decided rules in advance. These guidelines define what is not possible, but leave room for the possible without specifying more. Here is an example of a workshop in which 100 people at Bank of America organized themselves into teams and designed them within three hours.

Source

Another element can be gleaned from the illustration. It can still be necessary or at least helpful to centralize some decisions. The overarching corporate strategy is THE example of this. These and other governance decisions are coordinated centrally and the individual units must then act within the specified guidelines.

4 Ashby's Law still applies.

The requirement for the necessary complexity of the system is also present in an organization with a large number of independent units.

Complexity is distributed, it lies with the units instead of in a center of coordination. The opportunity lies in the fact that the reaction to a stimulus then takes place where the local knowledge enables a better response. However, this also creates a challenge. This consists of being able to share some information with everyone as quickly as possible. This can be achieved through central coordination or through a process that ensures this.

Question for you

Did the organization "de-escalate"?

If yes, how did you do it?

If no, would it have been better?

We are giving away the book "No Rules rules" by Reed Hastings and Erin Schmidt to everyone who comments here. The two describe how Netflix has simplified its organization step by step. It's not about agility or frameworks, which is perhaps what makes the book all the more worth reading.

Write a comment