Many projects that we accompany as coaches start with a customer calling us or sending us an email. Lately, the core statement is usually "we want to do Scrum" - sometimes more, sometimes less specifically expressed.

As an agile coach, the focus of my work is on familiarizing teams with agile working methods and coaching them in their implementation. For my colleagues and me, this also includes the question of whether Scrum is the right framework for precisely this project and this team. Since the invention of the user story at the latest, we know that the customer can describe the benefits they want very well, but that we can still talk about "how do we get there?".

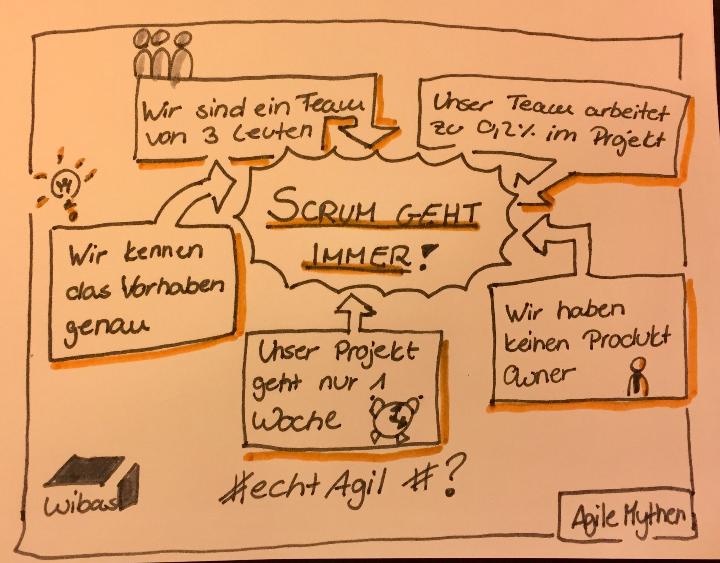

At this point, it should be said in advance: Scrum is not always the best method of choice!

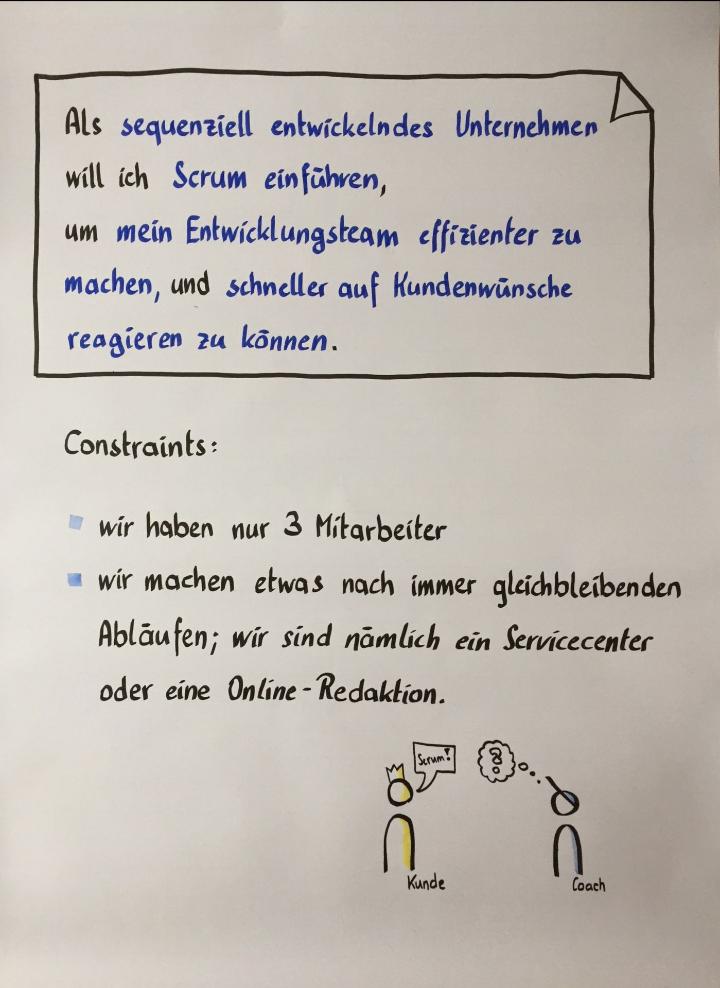

As a customer, I want to introduce Scrum

As a customer, I want to introduce Scrum

So my first question is: "Dear customer, what do you need?" - and the second sentence is usually: "Aha, and now tell me a bit about what you do and how you've been working so far"

The simplest exclusion criterion first:

To ensure that the three roles defined in the Scrum framework are properly staffed and separated from each other, and to maintain a reasonable relationship between the roles, Scrum is only recommended for development teams of 5 or more people. - Product Owner and Scrum Master are not yet included.

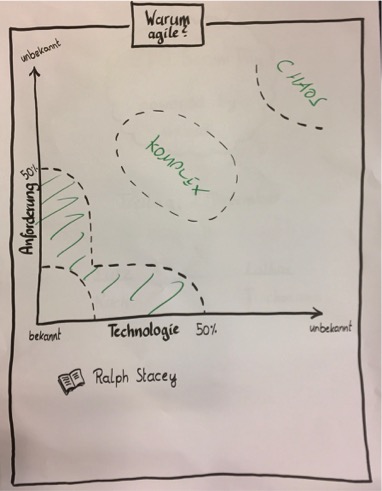

If this criterion is met, it gets a little more complicated: we try to determine which framework best fits the client's situation. To get an initial overview of when which agile framework is appropriate, we like to use the Stacey matrix as a guide:

Depending on the extent to which the requirements of the development team and the solution technology are known at the start of a project, four types of project can be distinguished.

4 Project types

For simple projects, the requirements and solution technology are known - for example, because we have already completed this exact work step countless times, activities can be planned very well in advance. McDonalds is building its three thousandth prefabricated branch on a greenfield site and can plan exactly after how many days which work step is required. Precise advance planning is possible because I know my work steps. Reacting to external changes is rather unlikely, I can typically transfer the planning 1:1 from one project to another. - In these projects, the planning and feedback loops that Scrum involves would represent unnecessary overhead. So Scrum doesn't fit here.

The opposite of this are projects in which neither requirements nor solutions are known at the start of the project - we call this situation chaotic. You will be familiar with this situation if you are involved in hypothesis-driven basic research. - Here, to the best of our knowledge and belief, it is not possible to estimate in advance how far you will get after a predetermined cycle of e.g. 2 weeks. This also makes the application of Scrum difficult - there are better things to do...

If requirements or solution technology are partially unclear, the main aim is to increase throughput. Stacey describes these projects as complicated. Examples of this are newspaper editorial offices, service centers or operations teams that debug. - In their area of application, it is primarily less about product optimization and more about throughput optimization; Kanban is a framework that covers the needs better than Scrum.

And then there is everything between complicated and chaotic. This area is complex. Complex projects already have initial solution hypotheses, but everyone involved knows that the hypotheses may still change to a certain extent during the course of the project. Nevertheless, the hypotheses can be developed step by step (i.e. iteratively) and, based on the feedback from my customers, I find out where further adjustments are necessary and where not. - We approach the bottom left corner step by step from our current position. This is exactly what we use Scrum for, by the way.

Let's imagine the areas in which Scrum does not fit, using an example

Optimizing throughput with Kanban

Let's take the example of a newspaper editorial office. Newspaper editorial offices typically work in cycles - daily newspapers in a daily cycle, weekly newspapers in a weekly cycle, etc.; thanks to the credo "nothing is as old as yesterdays newspaper", editorial offices are primarily oriented towards flow. The sequence of an editorial cycle usually always looks the same, for example as follows:

- At the beginning, there is an editorial meeting in which the overarching theme of the issue and/or the individual topics of the upcoming issue are discussed. At the end, there is a (prioritized) list of articles that should appear in the upcoming issue.

- After all editors have discussed the articles, individual team members pull articles that they would like to work on. The first step is to carry out preliminary research.

- In a second step, the editors arrange expert discussions or interviews. This step can be skipped in individual cases - for example, if it is a commentary or a gloss.

- The article is then finalized.

- While the editor was writing his article, the media editorial team prepared a suggestion of suitable images for him to choose from. The person responsible for the media editorial team was at the editorial meeting and therefore knows the topic of the article and basic key points, such as the format and size of the image to be selected.

- Once both are combined, the articles go to the proofreading department.

- If the proofreading department gives its approval, the articles can go into layout.

The solution is always the same. However, the requirements (= topics) always change within a spectrum during the editing process. If you follow the Stacey matrix, this is a classic example of Kanban - but why?

The articles are different, so copy-paste is not possible. The task is not easy.

However, in the context of an editorial team, I don't have to discuss in detail how the editors could solve their tasks. The tasks of backlog refinement, preparing and breaking down topics, also require much less or no space at all. - Scrum therefore creates an overhead for this scenario.

The aim of an editorial team is to optimize the flow of articles; Kanban shows us where bottlenecks occur in our process. If my Kanban board shows me that articles are piling up before the proofreading department, for example, I realize that it makes sense to help out people from another department that is doing an above-average job in the proofreading department.

Not all companies write newspaper articles - true. However, the example can be transferred 1:1 to other areas of responsibility. Experience has shown that Kanban is also suitable for areas in which the flow rate is the most important parameter, i.e. for bug management or for other areas in which ticketing systems are used today.

The other extreme: I have no idea what my product could look like.

In 2010, Steve Jobs stands in front of a select auditorium and explains that he has asked himself whether there are Space for something between smartphone and laptopwhether people need something. That was about 10 minutes before the CEO and senior managers realized that they had to get an iPad because that's exactly WHAT they always wanted. Steve Jobs also describes in this presentation what seven basic requirements he had for this potential product.

"As a CEO or senior manager, I want to know what a new product, smaller than a laptop but bigger than a cell phone, has to be able to do in order to... well, why do I even want this thing if I don't know what it should be able to do?"

Experience has shown that other frameworks are better suited to formulating and "testing" these hypotheses than Scrum, such as design thinking. Design thinking takes the hypothesis that a product could need a smaller laptop and a larger smartphone, tries to develop a series of prototypes within a very short space of time and collects customer feedback based on this experience. At the end of the design thinking process, teams know the most important functionalities for the customer. In the example that there is a market for products smaller laptop and larger cell phone, Steve Jobs presents these in the video:

- "Browsing the Web"

- "Doing E-Mail"

- "Enjoying & Sharing Photographs"

- …

- However, I can reassure all Scrum enthusiasts at this point: once you have created your hypotheses and "tested" them on your target group and the hypotheses have stood up to scrutiny, you are out of the chaotic area; then you can continue to "scrum".

Comments

Write a comment